Here’s just one brief memory from the Swans100 survey:

Brentford away. 2000ish. A drunk Swans fan kept climbing on the advertising and the police kept telling him to get down. In the end they lost patience and grabbed his arms to lift him out. Cue chaos. Fans around him grabbed his legs and tried to pull him back. There was a surge from behind me as people rushed to help. I was swept off my feet and pushed forwards. The police had their batons out and were hitting those holding on to the fan. I was getting pushed closer and closer to the police hitting out. I thought **** and elbowed my way out of trouble. Anon. 38

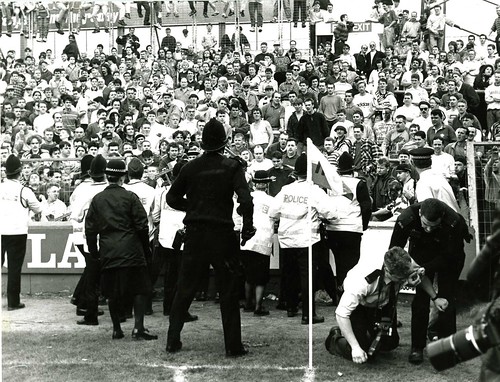

Even though the actual violence was usually relatively minimal, hooliganism defined how many people saw football in the 1970s and 80s and it could make a trip to the Vetch or a Swans away game a scary or an exciting event, according to your point of view.

Hooliganism, however, developed rather late in the game’s history. Before the 1960s, it was a rare event and normally limited to an isolated punch up in the crowd or a drunk fan running onto the pitch to remonstrate with a player or the ref. In 1934, the ref was even pelted by oranges by Swansea fans at a home game against Swindon.

Occasionally, the trouble was more serious, as the poorly-refereed 1923 West Wales Senior Cup Final between Llanelly and Swansea Town showed. The South Wales Echo (2 May 1923) reported

Immediately the final whistle sounded hundreds of spectators from the cheap side ran on to the playing pitch, shouting epithets at the referee who eventually had to leave the ground under the cover of darkness disguised in the uniform of a police officer … with trouble brewing a number of police officers, some of whom were in plain clothes, assembled near the entrance to the dressing rooms. … [The referee] was hustled as he walked off the field, and had only just disappeared into the official quarters when the main portion of the excited crowd reached the entrance. For a long time they set up a menacing attitude, while there were a few bouts of fisticuffs between supporters of the respective teams and the police had to interfere. All attempts to disperse the crowd were unsuccessful until police reinforcements … arrived on the scene, but it took nearly half an hour to clear the ground. In the meantime the referee remained in the dressing room, while attempts were made by the crowd to force the side doors near the main gate, and these had to be protected by baulks of timber.

However, there was perhaps more trouble than a scan of the newspapers suggests. Swansea Town’s visit to Millwall for a 1926 FA Cup 5th-round tie is remembered by supporters as being marred by fights with London dockers, yet nothing of the kind was reported in the Welsh press.

In 1926, with Swansea playing in London in the FA Cup semi-final, one fan found himself arrested and then fined for possession of a revolver. His excuse was that he had brought it ‘for safety as he was going to the cup semi-final’. Was that out of a genuine fear there could be a trouble? That man was one of two Swansea fans arrested that day. The other was cautioned for pushing people off a payment. In an interesting contrast, over fifty undergraduates in London were charged that day with drunk and disorderly behaviour following the Boat Race.

It was not until the 1960s that trouble became more common. In that decade, crowds were dwindling and becoming younger. In a more affluent society, older men had more leisure options than before and standing on a cold terrace was unappealing to some when at home there was a tv, new carpets and maybe a car to go out for a spin in.

With few older fans around, the younger fans could misbehave more and youth culture itself was growing more aggressive from the 1950s, as the Teddy Boys and Mods and Rockers showed. Younger fans had more cash too than before the war and this enabled them to travel to away matches, something that was rare before the war except for derbies and big cup matches. More away fans meant more opportunities for trouble. The special trains that took them to matches became hotspots for trouble.

The 1969 Welsh Cup final was one of the first Swansea games where this new culture became apparent. Around this time, there was a change in attitude towards Cardiff City amongst Swansea fans. With the big English clubs now attracting support in Wales thanks to television, local derbies changed from being surrounded by a friendly local rivalry to an atmosphere where supporting your local team was a badge of pride rather than something automatic. This brought a decline in the wider regional loyalties that had seen Cardiff and Swansea fans have a spot spot for each other.

In the 1970s and 80s, hooliganism contributed to attendances falling across England and Wales. The Swans erected fences in front of its stands and football fans were caged in.

Some young fans began referring to themselves as crews and fighting, or the potential for fighting, was part of the whole appeal of the game. They were dismissed by the football authorities and older supporters as not real fans but that misunderstood the hooligans. These fans actually supported their team so much that they were willing to fight for it. Hooligan culture was also entangled with fashion and music. It was something of a way of life.

Most of the trouble was not serious and show, bravado and display were important parts of the hooligan culture. There was also something of a code of only fighting other hooligans, although this was not always stuck to. Only occasionally was anyone seriously hurt. Nonetheless, a Swansea fan was stabbed to death in a game against Crystal Palace in 1980.

The mid 1980s saw greater public anger at hooliganism, especially after the Heysel disaster of 1985. Policing became more interventionist and there were new powers to ban fans and controls on alcohol. Close circuit television was used to minimise trouble inside stadiums. To some extent, hooliganism went out of fashion too, as youth culture was swept along by raving and ecstasy.

The problem never went away, especially at games against Cardiff City, and there was a degree of pride amongst some Swansea fans at their reputation for trouble. With the club languishing in the lower divisions, it compensated for what happened on the pitch.

The club’s rise up the divisions and the shift to the Liberty Stadium saw hooliganism decline even further. Occasionally, however, there was still trouble outside stadiums.

Here’s some Swansea fans discussing the issue and looking for trouble for the cameras.

You can watch videos of hooliganism and football trouble here:

Swansea – Cardiff tensions in 2008

gotta say my most humorous hooligan encounter was at southend . i think it was 2009/2010….11 of us decided to go up by train (as 2 of our party worked for the railway and got us all £5 tickets)..anyway we got off at southend station to be met by 20 or so southend hooligans (i use the word hooligans very lightly)..who decided to run at us . thinking we would run back into the station…we didnt and they panicked…from what i could make out there “top boy” ran sideways into a photo booth, where 2 of my mates wandered over and started scaring him to death to the point he was begging them not to hit him (nobody actually touched him)

i probably should have mentioned that all 11 of us are doormen, and we spent the next hour laughing at this pathetic attempt to put one over on us.